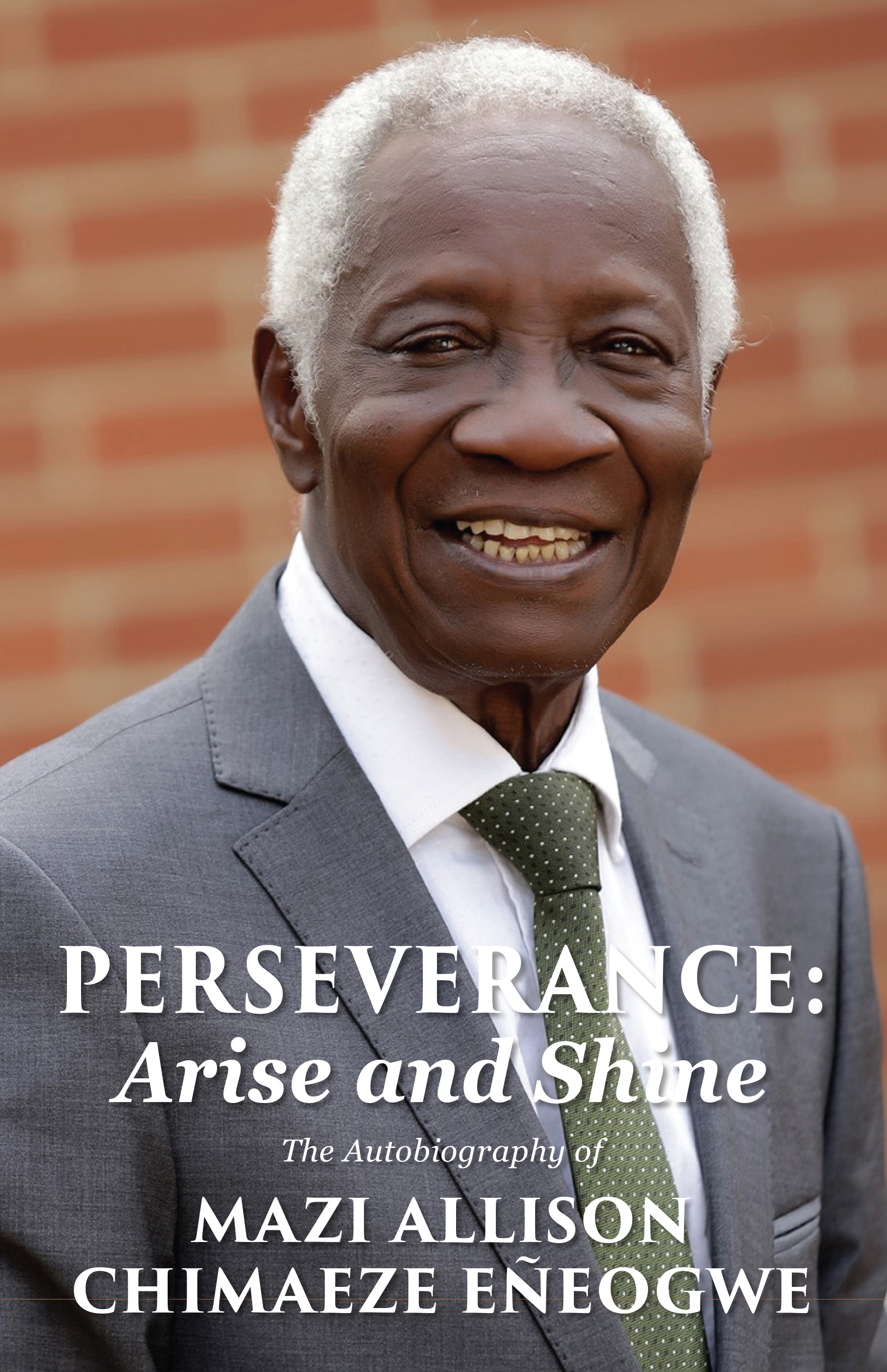

An excerpt from Allison Chimaeze Eñeogwe’s autobiography, Perseverance: Arise and Shine

From my radio, I knew by late 1969 that Nigerian troops began an unprecedented move towards the Aba axis. Aba-Ngwa people are as farmers and producing the best garri throughout Nigeria. This movement of the federal troops seemed to be total as they were combing from village to village. The majority of Ngwa people who had no money to feed themselves if they fled from their homes decided to take on the greater evil – mass surrender. The information from the radio revealed that those who surrendered were treated fairly. All they had to do was to hide in the bush or anywhere and await the retreat of the Biafran army. Then, when the Nigerian army advanced towards them, the people came out with white handkerchiefs in their hands, shouted “One Nigeria” and were safe from harm.

I went to Amepku Uratta, got my father with his wives and brought them to Umukalu Ntigha, Brother Levi’s village. By this time, he had also left Eziala Mbawsi – his in-law’s place – and moved to his village.

Other refugees living with us were moving northwards towards Umuahia, but my wife was very sick and I knew that if we went further, she was going to die. Going further meant getting to Mbaise area or Okigwe. In such a place, where were we going to get food? So, I called my father and told him that we were going to surrender now. I told him what I had been hearing from the radio, the modality of surrender and how those that surrendered were treated.

This time around, my father was afraid. “Do you mean that after we have managed all these days to escape death from Nigerian soldiers you want us to surrender now so that they will kill us?” he asked.

“No,” I replied. “The war has been going on for a long time and everybody is tired now. Most of the soldiers are now interested in whatever will end the war than what will protract it.”

“Chimaeze, if you say we should surrender, let us surrender. If they kill us today, I have lived longer than you and I have eaten more food than you. I will abide by your suggestion.”

Having gotten the approval of my father, I called everybody in Levi Okeogu’s compound – his elders, himself and all other refugees. I told them of the decision we had to take that very day, in view of the fact that federal troops were at our doorsteps. I had to be careful about making this thing open because I was afraid that someone might decide to report me to pockets of Biafran soldiers that were around the area who would not waste time in coming to execute me as a saboteur.

Since we were within shelling range of artillery guns, we could hear the booming sounds of all sorts of weapons, both small and large. Earlier, Levi had taken me to the bush with his brothers to map out our strategy. Thus, by 2 p.m. on 24th December 1969, we moved into the bush between Umukalu and Osusu Village and laid down flat in the bush. At about 4 p.m., we heard the marching song of the Nigerian army in Hausa, and I gave the order to shout, “One Nigeria” and rise up with handkerchiefs and move towards Osusu road and let the soldiers see that we were not armed.

Earlier in the day, we had buried my father’s double-barrel gun and other guns in the compound of the Okeogus, which we did not recover. I had to buy new guns for my father after the war.

As the Nigerian soldiers saw us moving in that convoy – male, female, boys, old and young – they were astonished. Some of them even knelt down and prayed to God and thanked him while others said, “So the war is ending?” Immediately, I came out from the bush with my wife and my two little children, my mother, my father and his entourage behind me. I was wearing a white long-sleeved shirt with white trousers. The soldiers shouted: “Welcome, my men. Food dey, water dey.” They instructed us to head to Okpuala-Ngwa hospital, where Isiala-Ngwa North Local Government Headquarters is located today.

Not long after the first detachment of troops passed, another detachment came by. I was wearing my wife’s wristwatch – a Buler Swiss watch – the one I had bought for her for our wedding. One soldier approached me and quickly removed the wristwatch from my wrist and it fell. Immediately, two of his colleagues picked up the watch from the ground and said, “Sorry, teacher.” One blew the sand off the wristwatch and put it back on my wrist. “We are sorry, teacher,” they repeated.

According to these kind soldiers, they had been in the bush for three years now praying that the war would end. Now that the people were coming out to surrender, their greedy colleague wanted to treat them badly. One of them warned the offender that if he engaged in such misconduct again, he would kill him. His partner nodded in confirmation of the threat.

They ordered the soldier to apologise to me, and he said, “Sorry, teacher.” I am sure it was the way I was dressed that earned me the name, “Teacher”.

We marched to Okpuala-Ngwa hospital where thousands were already gathered, loosely surrounded by some Nigerian soldiers. Immediately I settled down, a soldier came towards me and saw my radio – it was a Philips. The soldier told me that as soldiers, they took anything they desired from any refugee – radios and other valuables – but he had vowed that he would never take anything from the owner simply because the situation permitted it. So, he humbly requested to buy my radio. I told him that it was alright but that, since it was getting late, he should come over the next morning so we could talk about it.

The following day, the soldier came as arranged. He was not alone. The night before, I had made enquiries in the camp and I was told that I was fortunate I passed through the front and came in here with a radio. I was advised to quickly do away with the radio before I was accused of using it to communicate with Biafra soldiers. Throughout that night, I was afraid that what I had been warned about may occur.

I asked the soldier how much he would pay for my radio. The other soldier opened his bag and brought out a new radio exactly like mine. He was just there to advise on a fair price. “Talk truth for God, how much did you buy this radio?” my “customer” asked him. The soldier replied that he had just returned back from “pass” to Ibadan and that “truth for God”, he had bought his radio for 15 pounds.

I didn’t argue with him over this position and the buyer said he would pay me 15 pounds. I had been expecting to get five pounds at most. The soldiers left and in less than ten minutes, the buyer returned and gave me 15 pounds of Nigerian currency. That was when I discovered that Nigeria had redesigned the currency during the war. The money felt like a thousand pounds and marked the beginning of my financial recovery.

The Biafran currency was, however, still a legal tender among us in the camp.

We stayed in the camp until 31st December 1969, when they told us to go back to our different homes in the areas that had been liberated by Nigerian soldiers. So, on 1st January 1970, we started our journey back to Egbede.

PERSEVERANCE: Arise and Shine is about an “Iron Man of Action” who rose from being an apprentice electrician to a top industrialist.

At 18, young Mazi Allison Chimaeze Eñeogwe dropped out of school for lack of funds and moved to Port Harcourt where he became an electrician. His uncommon ingenuity made him stand out, and he rose fast in his chosen career, which was truncated by the civil war in 1966, during which he had to cross enemy lines for trade. Once the war was over, he settled in Aba and got involved in different industrial ventures. His faith as a Jehovah’s Witness always put him in good stead before people, and his sense of humour has seen him through many dark days.

PERSEVERANCE: Arise and Shine chronicles this proud Ngwa man’s challenges – sell-outs, fraud, kidnap attempts, false detention and a two- year self-imposed exile – and how he has come out of it all still holding his head high.

Available on Kindle HERE.